This is the first in a three-part series on voting and voting systems, and how to empower the citizens of a nation. This post discusses the problems we have. The second post covers how to improve elections of a single office, and the third post talks about gerrymandering and how we can avoid it.

I’ve become more and more obsessed with electoral systems recently. Winston Churchill once said, “Democracy is the worst form of government, except all the others that have been tried”, and that seems to ring true in a lot of ways. We can imagine lots of governments that are worse than democracy, but even our own democracy makes us feel like we aren’t being heard or represented. That’s not by accident.

They Say College Is Good For You

The Electoral College is the body that elects the President. it consists of 538 members, and each member corresponds to either a district or a state of the United States. The District of Columbia also gets three votes (as if it had a Representative and two Senators, like all the other states).

The Electoral College exists because some of the Founding Fathers thought that a nation of farmers couldn’t be trusted to elect a new set of governmental representatives every few years. They created the Electoral College to dampen the effect of individual voters. Votes in the college are awarded on a per-state basis, so a state could be barely won, or it could be won in a landslide, and it would make no difference: the candidate for president still gets the votes for that state.

The Electoral College, of course, is why we can have a candidate for president win the “popular” election, which is named in a way that might make you think it’s a popularity contest, and another candidate win the “real” election.

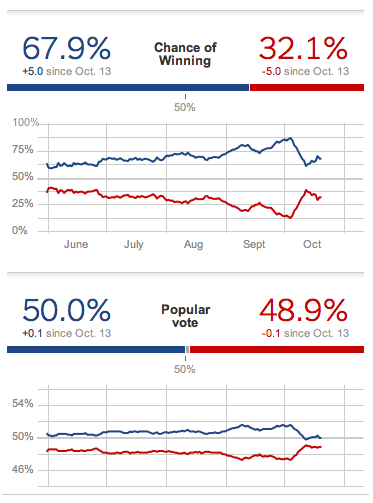

It’s also why we can have a situation like this:

From fivethirtyeight.blogs.nytimes.com, pulled October 20, 2012

From fivethirtyeight.blogs.nytimes.com, pulled October 20, 2012

Even though I’d rather Obama win than Romney, a situation like this is appalling and should never happen. For Obama to have a 67% chance of winning even though he only has just barely enough of the popular vote is a testament to how much the Electoral College dampens the effects of the voters.

Further, the free vote each state gets (for its Senator) amplifies the voice of people in small states over those in large states. Roughly every 670,000 people in Texas gets an electoral vote, whereas 330,000 Montana citizens get an electoral vote.

Your Old Friend Gerald

When discussing districts and the problems with the electoral system, we can’t ignore gerrymandering. Gerrymandering is drawing the borders of a district to increase or decrease the voting power of certain people in that district. A great example is Austin, where the citizens are squeezed out of having their own representative. The city is split into thirds, and each part of the city is grouped with large swaths of the conservative Texas countryside.

The primary problem is that the districts are drawn by the very representatives that will be elected in them, and this leads to two things. First, minorities in a region will get grouped with majorities in such a way that they can’t win districts, and second, the representatives have huge incentive to draw boundaries that are very safe for them to get elected in.

We could get rid of districts entirely, but they are useful. They provide an accountable person in office, who (ideally) comes from the same area as their electorate, and can speak for its residents in the legislature. Districts should be built around communities, with similar interests. There should also probably be a lot more representatives. Smaller voting bodies means the interests of the represented are more aligned.

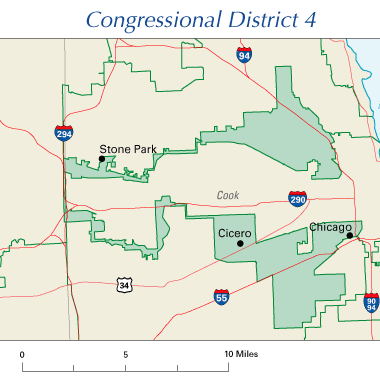

The 4th District of Illinois

The 4th District of Illinois

Smaller districts would also help in other ways. This clearly gerrymandered district in Chicago was carved out so that the Puerto Ricans in the north and Mexicans in the south can have a representative in Congress, and with more representatives, it might look like two very normal looking districts.

The Elephant and the Donkey

Americans also feel frustrated specifically by the two-party system, and it’s clear that it doesn’t satisfy us.

We saw this in the 2000s pretty readily. In 2006, The Zeitgeist was frustrated with George Bush, and voted a lot of Democrats into the House. In 2008, of course, they also elected Barack Obama. Nobody was happy, as you might expect, since most people don’t actually fall in line that well with our two given parties. The Republicans appealed to that dissatisfaction and won a ton of seats back in the House and the Senate in 2010. And so it goes, with neither side really satisfying the voter base, because the ideologies of the parties are too tight to appeal to such a wide group of people. This probably helps to explain why only 40% of Americans vote.

If you consider yourself a political extreme, you can’t even deviate from the parties, in fear that you’d be “throwing your vote away”, and causing the party you dislike to win the election. No Democrat can forget 2000, where Nader took 100,000 votes in Florida which would have tipped the scales for Gore. Even just New Hampshire, which was also taken by Bush with a smaller margin than Nader’s votes, would have been enough to give the election to Gore.

Inevitability

It turns out that a two-party system (and the other problems I’ve mentioned here) is inevitable because of the way our voting system is designed. We need ways to get more information about voter’s preferences and find a way to empower more voters.

Be sure to check out parts two and three of this series. They describe how we can work to fix these problems.