This is part two in a 3-part series about how to change our electoral system for the better. The first post discusses the problems that our voting system creates, and the third post talks about what we can do about gerrymandering.

In the previous post, I laid out three really big problems with our current electoral system:

It makes some people quiet and some people loud through the electoral college.

It encourages gerrymandering by giving the wrong people the wrong incentives.

Over time, it results in two parties.

To solve the Electoral College problem, we should just get rid of it. I’ll address how to fix gerrymandering and redistricting in the next post. In this post, primarily, I’m going to address the third problem, where we end up with two parties over time. The two party problem is the direct result of voters getting exactly one vote. Having one vote is, of course, better than having no votes, but it could also be much, much better.

Well then, how many votes should people get?

We can give them as many votes as we want: one, or two, or as many as they want, or infinite. Each of these changes has drastic effects on the voting system, and some of them are very desirable.

I’m going to run through a few voting systems that can help us elect a person for one office, such as the President of the United States (topical!) in this post, and in the next post, I will discuss how we can make a body of representatives in a legislature be more fairly elected.

First Past The Post

First Past The Post is the system that we have now. The first candidate to reach 50%, or simply the one that gets the most votes, wins. This is the most obvious choice, but it can also have some unintended consequences.

If you give everyone one vote, then the only reliable metric you can judge is a voter’s first choice. Since the voter’s choice is an incredibly rare resource, they’re going to use it as carefully as possible. This means they’ll be afraid to use it in an experimental capacity (like voting for a third party candidate, or a candidate that is clearly not going to win), deciding instead probably to just stay at home.

In this system, voters tend to use their vote to prevent one candidate from winning, rather than to try to get a particular candidate elected. For example, a libertarian in America might want Ron Paul to win the election, fearing that Romney isn’t fiscally conservative enough, but they would probably still vote for Romney, to make sure that Obama doesn’t win.

This is how you end up with two parties. Even if you start with a large number of parties, only a few are going to stand out in that crowd. As elections continue, people will abandon their smaller parties and join the bigger ones until there are only two left and they can not further consolidate. Historically, FPTP gives us two very narrow parties, with no clear way for third parties to break in.

FPTP can also be especially harmful in smaller elections, like local ones. If there are three candidates, there is a scenario in which the winning candidate got 34% of the vote, and the two losers got 33% each. This means that a healthy majority (66%) didn’t want the candidate that actually won the election.

Approval

If you give voters as many votes as they want, you have an approval system. With an approval system, as a voter, you would just check off every candidate on the ballot that you agree with. You wouldn’t be able to vote for one candidate more than once, but you could vote for all but one, for example.

Approval solves several problems. First, voters can support a third party without fear that it will cause someone they don’t like to be elected. To use the resource analogy from earlier, the approval system removes the scarcity of votes, which both allows people to be more experimental, and lets them be more honest about which candidates they want in office, without any external pressure.

This method of voting mostly provides information about how popular parties would be, and it lets the state to allocate funds accordingly. In America, 5% popular vote is a crucial number for a party to hit: it makes them eligible for matching funds. It would be way easier to hit this number if voters didn’t have to worry that the other acceptable party might lose to the unacceptable party as a result of their actions. And of course, over several voting cycles, approval voting allows a third party to gain attention without a voter ever having to stop supporting one of the major parties.

The last benefit to an approval system is that you never need to wonder how much of the population disapproves of one of the candidates, like they might in our local election example above. If none of the candidates can even convince 50% of the people in a population that they are worthy, you know that you have a very big problem.

Ranked Voting Systems

The final way to usefully elect a single candidate is to rank them. Ranks have to be in sequential order, two candidates can get the same rank, and not all candidates have to be ranked.

This voting system gives us flexibility. Once we have all of this information about the voters’ preferences, we can use a few different things to actually select a winner. The most simple thing we can do is tally up all the votes, and have the candidate with the lowest rank elected.

We can get weird, and use a Condorcet system: in this system, the winner is the candidate that defeats all of the other candidates in one-on-one comparisons. Condorcet is a particularly interesting and strange voting system because we can end up with a rock-paper-scissors situation, where Candidate A beats Candidate B, Candidate B beats Candidate C, and Candidate C beats Candidate A. Since it can be broken in this really simple way and understanding it is a little more difficult than other systems, it’s not really an ideal solution. It does have the huge benefit that if there is a Condorcet winner, you at least know that voters would choose them in every possible scenario (one-on-one with any other candidate).

Lastly, we can do instant runoffs: since we know which candidates the voters would have elected for if their top choice wasn’t available, we have enough information to determine who would win if a given person was taken out. If no candidate has more than 50% of the vote, we can take out the worst-ranked candidate until we have one that has a simple majority. A lot of local elections in America do run-offs a month after the November election because they don’t have a clear winner. This would completely eliminate such situations, and save everyone a little time and money.

Simulations

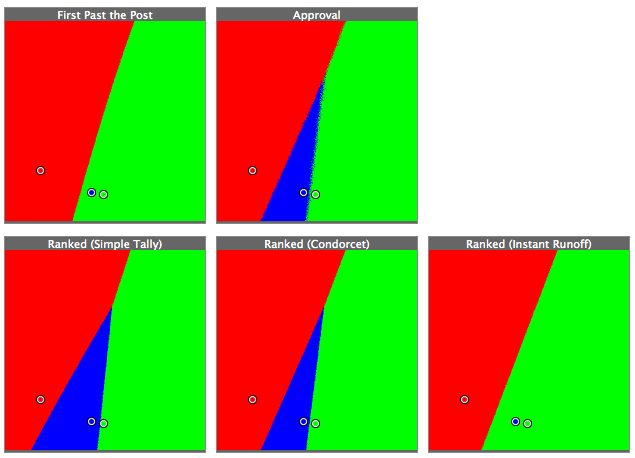

We can also simulate how people would act in certain situations, and we can see what effects these policies have on voters. Ka-Ping Yee did a series of simulations on his site, zesty.ca, and the results are interesting. I encourage you to read it all, but I’ll include one example below.

We can see that in a First Past the Post system, nobody votes for the third party when another person is clearly going to win. As you change the systems, though, that voters for the third party increase. Also, interestingly, having a third party on your side of the map can actually cause your opponent to lose, which makes sense. More people are likely to agree with you and the third party on your side than those that disagree.

Let’s vote

My personal favorite of all of these methods is the approval system. It’s simple, clear, easy to understand, and helps people voice their opinions about third parties. The only way to get more people to vote in this country is to give them better ways to be heard.

Be sure to check out parts two and three of this series. The first post discusses the problems that our voting system creates, and the third post talks about how to elect candidates for a chamber full of representatives, like a legislature.