I’ve been talking to a few friends about the iOS 6 maps; specifically what they added, what they took out, and who’s gonna be mad as heck about it.

“A step back”

A friend of mine keeps using that phrase to describe the new Maps app, but I don’t think that’s entirely right. For those that haven’t heard about the changes yet, they’re switching to using their own data instead of Google Maps data, adding turn-by-turn directions, and real-time traffic information and possibly most importantly, removing transit directions. For transit directions in iOS 6, other apps can register as transit apps for various cities, and it’ll present you with that list of apps when you’re in a city and you need transit directions.

Apple historically doesn’t like to be reliant on a company the way they were with Microsoft with Office and Internet Explorer or the CodeWarrior folks back in the day, so they made iWork, Safari, and Xcode, just so they could update those at their own pace. In that vein, the disuse of the Google maps tiles seems really straightforward, but I think there’s more going on.

Transit

The removal of transit routing from the new app is a huge mistake. All of that data is available already openly available for most cities (because it powers the Google maps transit routing). You can read about that specification here. If I had to guess, I’d say it was only an issue of time that caused it to get left out in iOS 6. I’d be incredibly surprised if it weren’t back in iOS 7.

Turn-by-turn

Android got turn-by-turn directions almost 3 years ago, and it seems that Apple just wasn’t allowed to take advantage of that kind of functionality from Google, for some reason. To gain any new features at all, it seems, the deal with Google had to be completely broken, and a new Maps infrastructure would have to be built. So they did, and it took them a few years, but now we have turn-by-turn and real-time traffic data at the expense of transit directions, and data density.

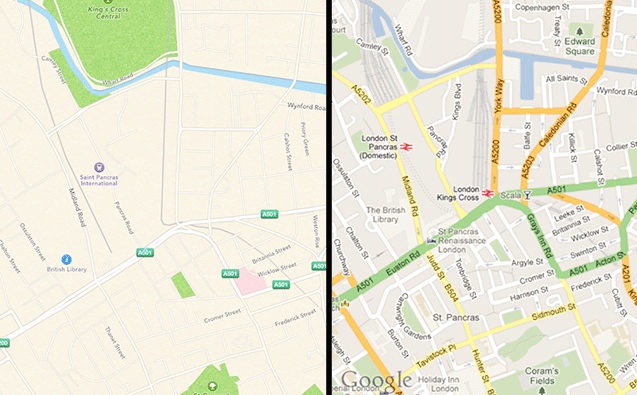

By now you’ve certainly seen an image like this:

I prefer the Google map for sure. Better information density, more clear, generally richer. The problem for Apple here is data. Before Google maps, basically one company had any kind of digital map data that they were willing to license, and that was Navteq. They powered Mapquest, Yahoo! Maps, Google Maps, and anyone else trying to play in the market. However, in the mid-2000s, Google made a really smart decision and outfitted cars with cameras and GPSes, and they went around the country collecting not only street view information, but also street information. This let them build up their own map graph, and made them no longer reliant on Navteq, and let them do whatever they wanted with the data, including turn-by-turn (disallowed by the Navteq licensing terms).

Which brings me to the possibly most interesting about the new Maps in iOS 6, which is the real-time traffic data. If traffic data is really being captured from all iPhones (while they’re doing turn-by-turn only, I’d imagine, just so they could save a little battery life), they would have an incredibly rich dataset of how big roads are, which directions they go in, when new streets are put up, and when old streets are blocked off, and if they could get this data from Waze (who is their partner for the real-time traffic technology) they could build a map dataset to rival Googles, and then they could enable the richness of context that Google provides for its map tiles.

Apple’s certainly is not a data company, but they definitely seem to be moving in that direction, with Siri (which needs a tremendous amount of voice data to be accurate) and possibly these new maps, and that could be exciting.

WWDC this year has been excellent. Cool APIs, cool folks, and I actually managed to write a decent amount of code during.

The labs were also incredibly helpful. I fixed a static analyzer bug that I’ve been having for months.

PodcastTableViewController *ptvc = [[PodcastTableViewController alloc] initwithSearchedFeed:feedData];

The static analyzer was complaining that I was releasing this object too many times. I went over it a dozen times and couldn’t find why it was wigging out. Turns out, it’s the lowercase ‘w’ in the method name. Unless it’s uppercase, the LLDB thinks that the prefix is ‘initwith’ instead of ‘init’ and it doesn’t assume it’s returning a retained object. Which is apparently how memory management in Objective-C really works.

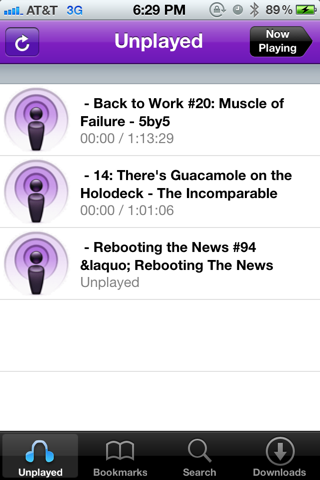

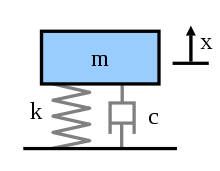

In 2011, I made a web platform and iPhone app for syncing podcasts called Fireside. Its name is actually really hard to search for, so I may change it and rebrand the app, but for now, I wanted to share a little bit of the design process of making the app.

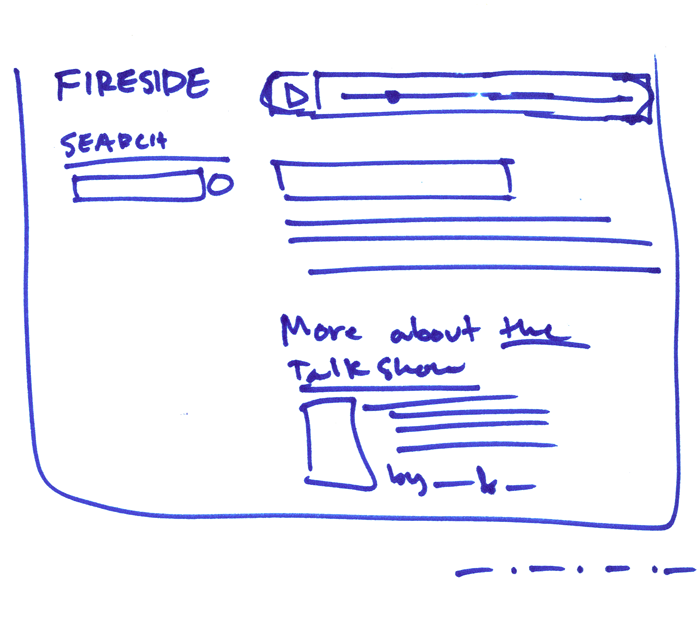

Web

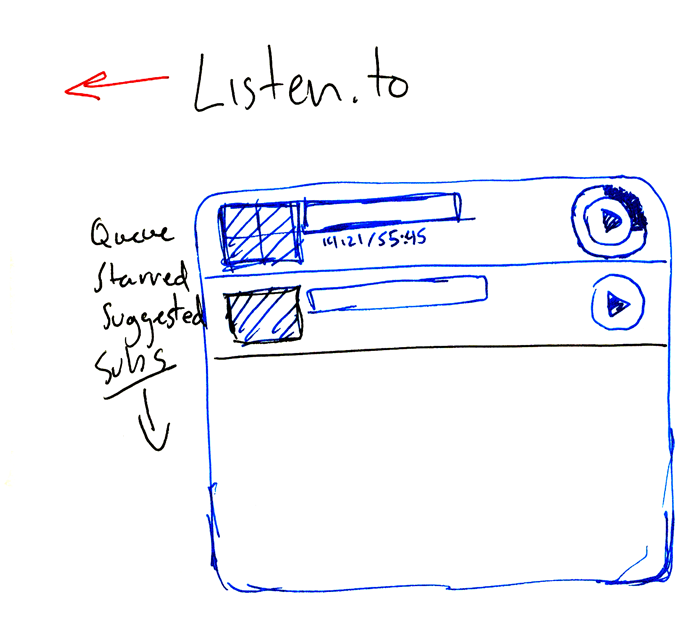

The website is pretty simple, and hasn’t changed much since the first few sketches.

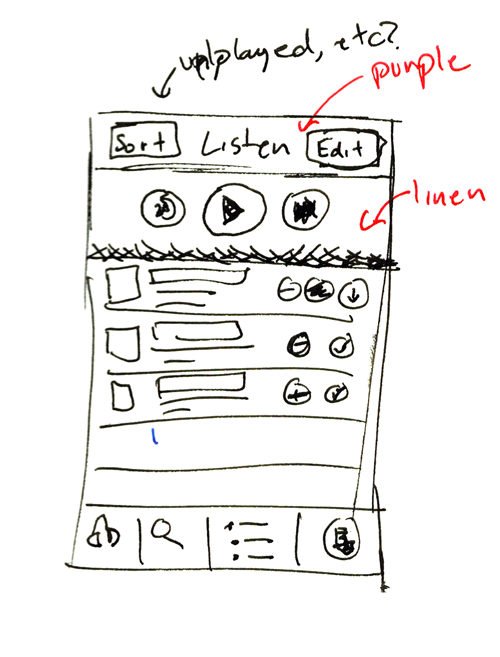

When I was first working on the app, I wanted to call it “Listen” and center it around a metaphor of headphones. “Listen” would have even less Googlability than Fireside, so I ended up ditching that. Having iTunes-style progress bars that go around the play button was an early idea, but didn’t end up making the cut because having a more traditional progress bar was easier for the user.

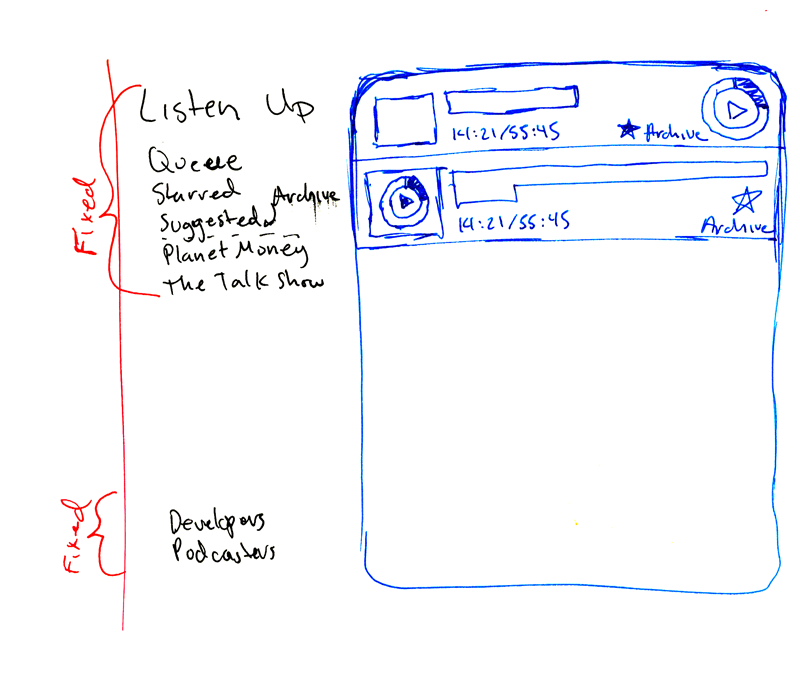

I tried focusing the app around an idea of a queue, but that was too programmer-y, and ended up just calling it the unplayed list. Also, the fixed menu on the left didn’t work, because it didn’t scale with a large number of podcasts.

I really like doing quick sketches in a permanent marker, since the fidelity is super low and you can’t get lost in filling in the details or having to come up with fake copy. I’m very sure I straight-up stole this idea from someone, but I can’t for the life of me remember who it was. Either way, it’s great, and you should steal it, too.

Javascript errors-of-intent are super cool

Javascript errors-of-intent are super cool

iPhone App

I thought about having a main playback control area at the top; it would be sort of an inset area that would have a linen background (I’m the only developer that actually likes linen as the bottom layer of the OS, sue me) and playback buttons that would let you quickly play, skip, and seek through the podcast.

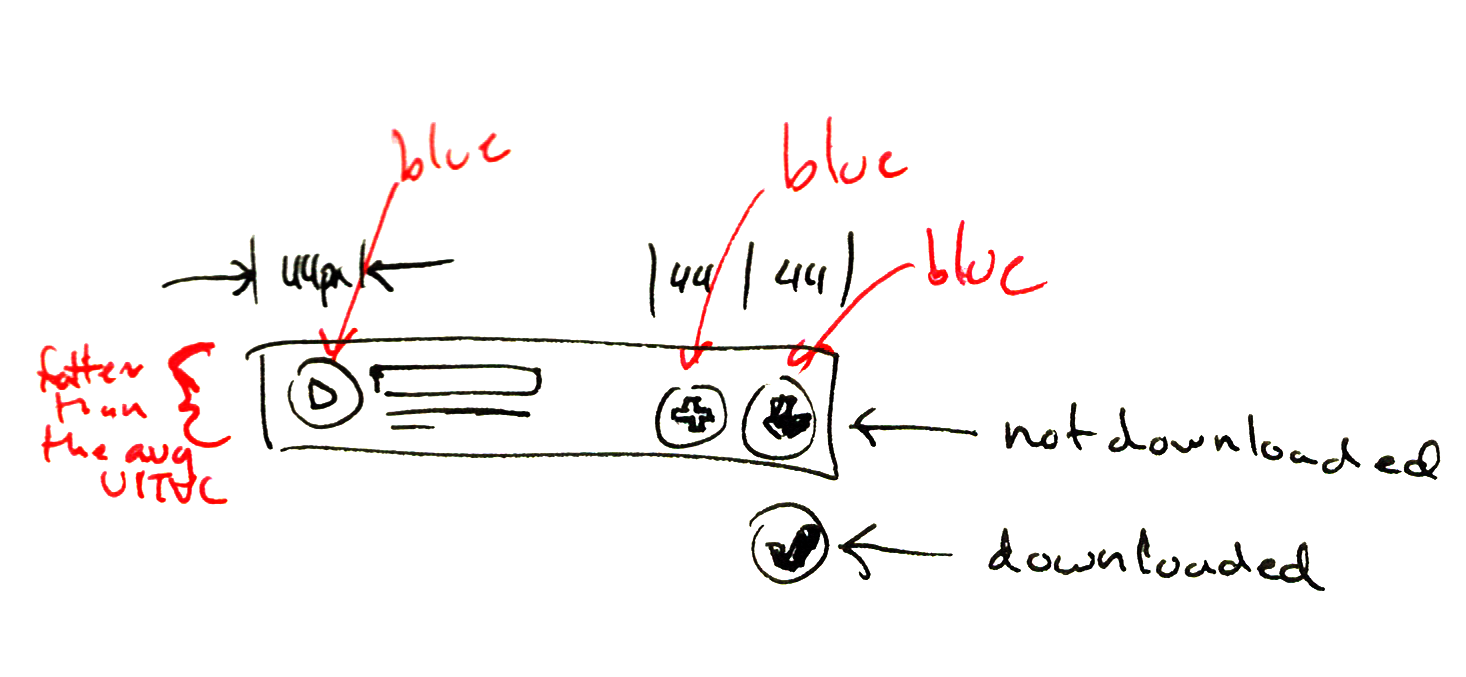

I also sketched out a table cell with buttons on it, for adding to your queue, downloading, and playing. The buttons ended up being too small to really be effective, and the cognitive load on the user of all those buttons became overwhelming.

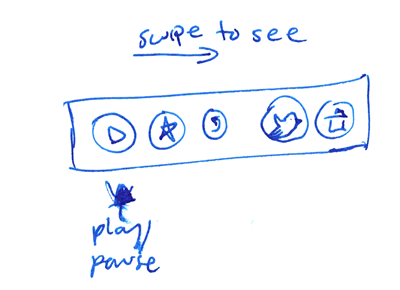

To solve both of those problems, I ended up choosing not to have a playback control area, and instead stealing Loren Brichter’s swipe-to-action menu. This didn’t make it into 1.0, but 1.1 had the menu. Teaching users that it even exists is a difficult problem, one for another blog post.

At this point in the development of the app, I had the syncing working, but only just barely. I didn’t have a player screen yet, so all play/pause actions were controlled by the button in the top left. Once I fleshed out the podcast table view cells, the app slowly started to take shape.

On this week’s Build & Analyze, Marco mentioned that sometimes his calendars in iCloud weren’t updating until the app itself was open. I’ve had a fair bit of trouble with iCloud so far (my iTunes match playlists are currently missing from my phone, and my bookmarks seem to be a total mess at the moment), and I’ve noticed this behavior as well. It’s hard to trust a new piece of technology until you really understand how it works, and iCloud especially is completely impenetrable.

I set out to rigorously test iCloud and try to understand it’s underpinnings, both in the OS and in the clowncloud. What I found, perhaps unsurprisingly, is that it mostly works as expected. My Mac runs OS X Lion 10.7.3, and my iPhone 4S and iPad 1 both run 5.0.1.

Photostream

Photostream only works on WiFi, exactly as it’s billed. I took a photo on my phone while it was on 3G, waited a few minutes with my eye on iPhoto on my Mac, and didn’t see anything. I switched the WiFi on the phone on, waited in Settings.app, and saw the photo show up in iPhoto after a few moments. I also was curious to see if photos would upload with the screen off, so I took a photo with double-click shortcut, and turned the phone’s screen off immediately. The photo was added to my Photostream, just as expected.

Contacts and Calendar

I performed several tests with these apps. I varied things like the action (creation vs editing), the state of the app (active, suspended in memory, force-quit from the multitasking tray), and internet connectivity (3G, WiFi, wired). Here are the different tests that I did:

Created a contact on my Mac, with the Contacts tab of the Phone app open. I watched the contact get pushed and the view get updated with no interaction from me.

Edited the contact on my Mac with the app on my phone suspended, with WiFi on. I waited about a minute and a half, turned on Airplane Mode, and went to the Contacts tab of the Phone app. This edit did not propagate.

Created a calendar event on my Mac, with the apps not-yet-opened on my phone and iPad. I left WiFi on for a few minutes, on each device, before turning on Airplane Mode, and checking each device’s Calendar app. The event had been created on both devices.

Turned off WiFi and edited the event on the iPad, switched to Settings, and turned on WiFi. The change to the event showed up on all devices.

Did the same test again, but before turning WiFi back on, I force-quit the Calendar app on the iPad. Change propagated.

Retested Contacts, wondering if the failure was a fluke or a difference between Contacts and Calendar. I modified the contact on my phone over 3G, and watched it update in Address Book on my Mac. I also turned on WiFi on my iPad for a few minutes, turned it off, and checked the contacts, and it was updated.

Basically, any combination of factors I threw at it worked fine. iCloud can receive changes and updates when the app is force-quit, suspended, active, or not-yet-opened. It can also send updates if a device was in airplane mode, and gets a connection sometime later. The operative word, however, is can.

For some reason, test 2 failed. I’m not sure why the first backgrounded Contacts test failed. If Siri is any indication, it’s possible that iCloud is overwhelmed fairly often, and it doesn’t complete pushes. It’s also possible that pushes are ignored when the device is hibernating (which is how the iPad and MacBook Air can have sleep times of close to a month), but I was under the impression that it was built on the same framework as SMSes and push notifications, which you certainly can get while the device is “hibernating”.

Third-Party Apps

I don’t have any third-party apps that use iCloud. I tried to do some testing with FlightTrack Pro, but I couldn’t even get iCloud syncing to work when the connection was active on both devices. If you find anything interesting, please be sure to let me know.

Pages, Keynote, & Numbers

John Gruber mentioned in last week’s Talk Show (I listen to too many podcasts) that Schiller and the other Apple reps managed to get a flawless demonstration of Pages live-updating between Macs and iDevices, so I thought this was a new Mountain Lion feature, but it seems that Pages on the iPad and the iPhone can do this today. If you have one document open on both devices, you can make a change on one, it’ll show you an alert telling you that the other device is editing and when you dismiss the alert, the changes show up, live, on the second device.

I have a 27” iMac and a 27” Thunderbolt Display on my desk. These monitors are (unsurprisingly) huge, and their footprint is also pretty large. Between a keyboard, mouse, and trackpad as well as these two monitors, I was running out of space for notebooks and other reference materials, so I decided to clamp them to the desk and get their stands out of the way. There’s a pretty huge lack of material about this, so after scouring random forums, I found a way that works great.

To mount either monitor, you need two things:

Apple VESA Mount Adapter Kit (affiliate link) (one for each monitor/iMac, of course)

Ergotron MX Desk Mount (again, one for each monitor)

The MX is expensive, but it comes with a variety of mounting options and supports the ~30 pound weight of each monitor.

Assembly

All the tools you need are included in these two kits. I think the VESA mount adaptor is the only Apple product that requires any assembly, which entertains me for some reason.

Adaptor Kit

Place the monitor flat on its screen.

Slide the included card into the crack between the stand and the device to unlock the stand and reveal the 8 Torx screws.

Unscrew them, remove the mount, and attach the fitting with the same 8 screws you just removed.

Lay the plate on top of the fitting.

Screw in the top bolt. Until you screw the top bolt, the side bolts will not fit.

Screw in the side bolts.

MX Desk Mount

Attach the plates you need, depending on if you’re mounting to the wall, through a desk hole, or clamping to the side of a desk. I clamped it to the desk and I found that it’s easier to clamp it to the desk before attaching the monitor.

Attach the monitor.

Tighten the hex bolt in the arm to increase the tension and make the arm support the weight of the monitor. This hex bolt can be adjusted using the Allen wrench they give you and is coaxial to the arm. It’s hidden inside, so you just have to feel around with the wrench until you find it.

I have a pretty crappy particle board desk from Ikea, and the clamp seems to hold fast to it. I was a little worried that the stress from the mount would break the desk, but it seems to be okay.

If I’m typing very vigorously, sometimes the monitor shakes a little. Other than that, I’m very happy with my new-found desk space and with these mounts.

Get in touch via Twitter at @khanlou or via email at soroush@khanlou.com if you have any questions about the setup.

Syncing is an incredibly hard problem to solve. If you have a small operation, many people will tell you to try to work around it somehow, or to outsource your syncing to iCloud or to Google. I wasn’t able to find any resources when I was working on the syncing in Fireside, so I thought about the problem for a while and solved it in a pretty good way. This post won’t have a bunch of code to just copy and paste, but, rather, instructions and a framework for how to create a system that works for you.

Considerations

I’m assuming if you’re looking beyond iCloud and other such syncing services, you’ve already got a pretty complex problem to solve. Maybe you want a website where users can access their data, maybe you’re looking towards other platforms, like Android. No matter what, there are several considerations that you want to take into account when creating this system.

The basics are pretty straightforward. You need a language for the computers to use to talk to each other. I like JSON; it’s light, fast, and parsers exist for every platform. Other options are XML or even binary plists, if you’re working with a WebObjects server and serving data mostly to Apple devices. You need an API, which should be really well thought-through, since you can’t really control when your app gets updated by the user, and you’ll need to essentially support those API endpoints forever. And finally, you need to decide how much ephemerality you want your data to have. Twitter is a very transient medium, and so Twitter clients might not want to use data that’s more than few days old. Other platforms will need all of the data all of the time. A user might want a Basecamp client that always has all their data. This is a client side problem, but, nevertheless, deciding this will help you design your APIs.

The amount of data being synced

The first thing to think about when syncing is how much data a user might want to keep in sync. If it’s just a few preferences and text strings, it’s much easier to just serve them all of the data they need every time, than to try to figure out what data the device needs at a given point. This is how subscription syncing in Fireside works. Even a user with hundreds of subscriptions might be an an API call of a couple of kilobytes. Since the majority of the lag on wireless mobile networks is latency, a couple of KB of served JSON document is pretty inconsequential.

If you have any more data than that, you should start thinking about how to segment your data such that the device doesn’t have to download more data than it needs to. This kind of segmentation is usually done using time, i.e., only download data since the last time the client synced.

Also, consider the amount of data you want on the client. Twitter clients don’t (and reliably can’t) access all the data in your Twitter account, and Twitter is designed to show you what’s fresh and relevant, so it’s not even important for them to download old stuff to your device.

Quantization

The next step is to quantize your data. A quantum of data is essentially the smallest unit that needs to stay in sync. For a service like Fireside, these are the properties of the podcast, such as any detail about the user’s interactions with that podcast (i.e., stars, playback location, archival status, etc). For Twitter, it’s a tweet. Separating your data into units like this is probably already done, but it’s crucial for updating these units on the server in a way that assures the user’s intents are properly synched. We’ll discuss this more in conflict resolution.

Divorce the metadata from the data

Until Instapaper 4.0, the app didn’t show articles until the article itself was downloaded onto the device. This meant that the process was slow and the user had no idea how many articles were coming in until the app was done downloading the content of the article itself. Currently, as of 4.0.1, it shows the list, and lets the user know which articles haven’t downloaded yet. If you are syncing something with a significant amount of data (articles, podcasts, images), separate it from the metadata, since metadata downloads much faster, and you can present the user with that information before actually having it on the device. Something like tweets or Facebook wall posts are probably small enough to not worry about.

Offline data

Storing the data in a persistent way on the client side is crucial. It’s nice to pretend that we have always-connected devices, but many users live in rural areas with slower mobile networks, have bandwidth limitations, use non-cellular devices (like iPods and iPads), and are on planes and subways. I can’t count the number of times I’ve tried to use a service like Tweet Marker in an area with very high latency. It’s unbearable. Assuming that the server will always be available and will always be quick is a huge mistake. Clever usage of local databases and sync queues can make the user feel like your service is faster and more available than it actually is.

Queueing, offline syncing, and persistence

Not only should you worry about the data you read being available offline, you also should consider that the actions the user might take while offline. On the client, especially on wireless mobile networks, you can’t always rely on your HTTP connection successfully connecting. To solve this problem, you can queue the user’s intent to perform an action (like starring a tweet: I’m looking at you, Tweetbot), and only remove that action from the queue when you’ve seen that the HTTP connection has been completed. If your client is designed on iOS, using NSOperation and NSOperationQueue can make your life much easier, but it sort of behaves as a black box, and you have to use KVO to get any useful information out of it.

You also want to think about what happens when the user performs a bunch of actions (in the subway, for example) and closes the app, which gets quit by the system at some point. When the app opens again, the user will expect to see their actions having propagated across your system, so you have to store the users actions in a persistent way (serialized on disk) so that the system works the way the user expects. Offline actions aren’t strictly necessary, but can delight the user, and should at least be considered.

Conflict Resolution

Here’s where creating a sync API gets fun. If you have an offline, persistent queue, then the user might create conflicting states. She might change one of her objects A to a state B, at a point when the system doesn’t have network access; later, perhaps on a different device, she updates object A to state C successfully; and finally, the original device regains a network connection and tries to change the state of object A to state B. There’s several ways to handle this.

Do nothing. When the delayed state change B finally comes through, it overwrites the state C.

Last action wins. Sync intents come with a timestamp of when the user intended them to go through; if that timestamp is after the timestamp on the server for when that object was last changed, the sync intent is ignored. (NB: This is how Fireside works, and this is also why the quanta of Fireside’s podcasts are the properties about the podcast and not the podcast object itself. This way, the user can star a podcast on one device and update the progress on another, and because the timestamps of starring and progress are stored differently, both changes will go through as the user expects.)

Some other metric. You might have a

progressproperty that should always be at the furthest location. Check this on the server, and set the state of the object to whatever is appropriate.**Versioning. **With versioning, when a change to the state of an object conflicts with another change, the older change gets folded into the stack of changes and the user can return to it if she desires. I’ve heard whisperings that this is how iCloud works, but of course, we haven’t seen any access to these versions on the user side.

Prompt the user. Find a concise way of describing the differences, and then ask the user what they would like as the final state of the object. This is how MobileMe worked. I would recommend against this; I try to bother the user as little as possible.

Naming

What do you want to call your service? Sync implies keeping things in harmony; historically, it also has a bad rap. Sync is unreliable. Sync breaks. Sync is another thing to worry about. Apple used the word “sync” very little when debuting iCloud, opting for more active words like “push” and “send”. You might want to use the word “cloud”, if you don’t find that too offensive.

Redundancy

Your users are trusting you with their data. Having your server go down will make them unhappy, and losing their data will make them angry. Consider multiple forms of backup, security, and redundancy. These are annoying things for a small startup to worry about, but it’s better than losing all your user’s data. Netflix uses a tool called the Chaos Monkey that randomly takes down servers and services that Netflix relies on and generally wreaks havoc on their services. It’s excessive, but when half of the Internet died in December 2010 due to an AWS outage, Netflix carried on just fine, even if they did have a little lower bitrate on their movies. Netflix expected failure, and that helped them avoid it.

Canon

Where is the canonical copy of the data? In most situations, this is really easy to answer: it sits on the web server. If you are running a cloud storage or backup system, and you know that the user is only using one client device, the canonical copy of the data is on the device, and the server should never overwrite it.

Falling out of sync

The user’s data will fall out of sync, and this is a bug you will have to squash. You can try to correct it by providing the user with a way of clearing data out and redownloading from the canonical copy. You might use a hash or CRC to assure that the data is identical on multiple platforms, and create some kind of error correction.

Conclusions

Sync is a hard problem to solve, but it’s not impossible, and its benefits are obvious: it’s tremendously useful to users and can really differentiate you from your competitors. If there are things that I haven’t included in this short guide, please feel free to send me an email at soroush@khanlou.com or a tweet at @khanlou.

All pictures were taken with a T2i. You can find details about the the settings I used to take each shot in the caption of each image. These pictures aren’t modified or edited except for size and cropping.

On October 24th last year, I finally made it out to a Pennsylvania park called Cherry Springs. Cherry Springs is most notable for its International Dark Sky Park status. Because of its remote location, high altitude, and the fact that neighboring towns are all in valleys, it has remarkably little light pollution. It’s the first American Dark Sky Park, and the darkest spot in the eastern United States. It seems we can’t compete with the barren wastelands of the West.

I arrived at around 8, when it was already dark, set up my tent and met a few astronomers that were more serious than me. I took a couple of mediocre shots, and started to notice a red tinge around the Milky Way.

f/3.5, 30s exposure, ISO 3200, 10mm focal length

f/3.5, 30s exposure, ISO 3200, 10mm focal length

Terrified that something had gone wrong with the sensor in my camera, I asked one of my new friends if I could take a few shots with theirs. The tinge was there on their camera as well. I was confused, trying to figure out what would cause that to happen. While I was taking a picture of the Pleiades, I noticed a streak of red light coming up from the forest.

f/7.1, 30s exposure, ISO 6400, 10mm focal length

f/7.1, 30s exposure, ISO 6400, 10mm focal length

(You can also see Jupiter to the right of the red glow and a plane to the right of that.)

The streak turned out to be part of an aurora, which lasted about an hour during its most intense and continued to tinge the sky red all night. I’m not exaggerating when I say that it was one of the most gorgeous things I’ve ever seen.

f/7.1, 30s exposure, ISO 6400, 10mm focal length

f/7.1, 30s exposure, ISO 6400, 10mm focal length

This particular aurora was seen as far south as Missouri, which is pretty strange for an aurora. Later in the night, Orion rose, and I was able to get some pretty stellar (heh) shots of Orion too.

f/3.5, 90s exposure, ISO 800, 18mm focal length

f/3.5, 90s exposure, ISO 800, 18mm focal length

When I showed this to a friend who’s pretty into astronomy, he shared some cool insights. If we look near Orion’s genitals, we can see that there is a bright red nebula between his legs.

He showed me a real picture of the nebula, from a proper NASA telescope, and I put them side-by-side.

Even though I understand that space is a place, and that it really should always look the same when we get images of it, it still blows me away that the picture my amateur dSLR can capture what is so clearly the same thing as a serious telescope with a serious image sensor. Maybe that’s naïve, but it’s also beautiful.

The Javascript history is one of the coolest new features in HTML5. It lets us push things onto the history stack without loading a new page, and without using weird, hacky hash-bangs (#!, like Twitter) to keep our content crawlable.

It’s crucial in the Fireside web app because you want your podcast to continue playing while you browse through other shows and lists. I could probably accomplish the same general idea with a frame, iframe, or with URL fragments (the part the URL following a hash). However, frames are a hack, and break things like command-clicking to open in a new window, and page fragments break the web (which I plan on writing more about later).

How to use the API

Using the API is relatively simple. I’m using jQuery, because I’m not a masochist. First, you want to bind an action to the links that you want to intercept and load with Javascript. I made a CSS class for this, so that I can quickly add this to any link, but, of course, you can bind this to any selector. We pass the event e to our function, because we’ll be needing it. We will use .live() instead of .ready() because if we add more elements to the document later, we want them to also be bound to this function, and .ready() will not do that.

$(".load_ajaxy").live('click', function(e) {

Next, we grab the href attribute, and we check if the event has a metaKey being held down. If the user is holding down the Command key on a Mac or the Control key on Windows, we don’t want to execute any more code.

var thePath = $(this).attr("href");

if(!e.metaKey) {

We check to see if the browser supports the History API, and actually push the URL onto the stack. The URL can be relative or absolute. This API detection code is lifted from Mark Pilgrim’s now-defunct Dive into HTML5.

if(!!(window.history && history.pushState)) {

history.pushState(null, null, thePath);

}

Next, we stop the default action of the link (i.e., sending us to the page it links to), and perform an AJAX request to load the content from our server. I built a special PHP page that will parse the url, and return just the content area.

e.preventDefault();

$.ajax({

url: '/content/',

data: 'withPath='+thePath,

type: "post",

success: function(data) {

//load downloaded content and insert into document

$('.content').html(data);

}

});

You can also add fancy things like an indeterminate progress indicator or a semi-transparent cover to indicate to the user that the page is loading.

Complete Code

$(".load_ajaxy").live('click', function(e) {

var thePath = $(this).attr("href");

if(!e.metaKey) {

if(!!(window.history && history.pushState)) {

history.pushState(null, null, thePath);

}

e.preventDefault();

$.ajax({

url: '/content/',

data: 'withPath='+thePath,

type: "post",

success: function(data) {

//load downloaded content and insert into document

$('.content').html(data);

});

}

}

});

When the back button is clicked

The other component is what happens when the back button is clicked. We need to monitor the popState event, so we bind a function to it.

$(window).bind("popstate", function() {

var thePath = (location.href).replace('http://domain.com','');

$.ajax({

url: '/content/',

data: 'withPath='+thePath,

type: "post",

success: function(data) {

//load downloaded content and insert into document

$('.content').html(data);

}

});

});

One small note: the popState event gets fired in Chrome and Firefox (but not Safari) when the page first loads, so you have to deal with this. I use a bit that’s flipped that tells me that the page is fully loaded, which I check in the popState function. You can also handle this by not loading content in the version of the page that is served, but rather loading it with javascript in this popState function.

Browser Support

The History API is supported in IE 10, Firefox 6.0+, Chrome 13.0+, Safari 5.0+, and Mobile Safari 5+. If the browser doesn’t support it, my implementation still stops the default action and performs the AJAX request, it just doesn’t push anything onto the history stack.

Update (Aug 2012): I’ve made a class called SKBounceAnimation that handles almost all the heavy lifting for you. Check out the blog post and view it on GitHub.

UIScrollViews, which are the main elements that move in iOS, have momentum, friction, and bouncing built into them. To design an animation with just momentum and friction, we can use the simple, built-in ease-in-ease-out timing functions. To include a bounce, however, we need to switch to a more complex technique.

We could simulate this by using multiple animations. In the completion block of the “overshoot” animation, you could create another animation that bounces back the object back and you could do this a few times until you have all the bounces you want. A hack, essentially.

Theory

What if we could describe all of the motion with one equation, and tell the system to just animate just once along that path?

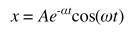

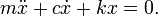

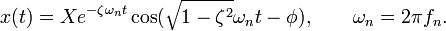

Fortunately for us, we can. In my previous post, I describe a mass-spring-damper system, which simulates the real-world motion of an object. Solving our mass-spring-damper for a system with an initial displacement and simplifying, we get this result:

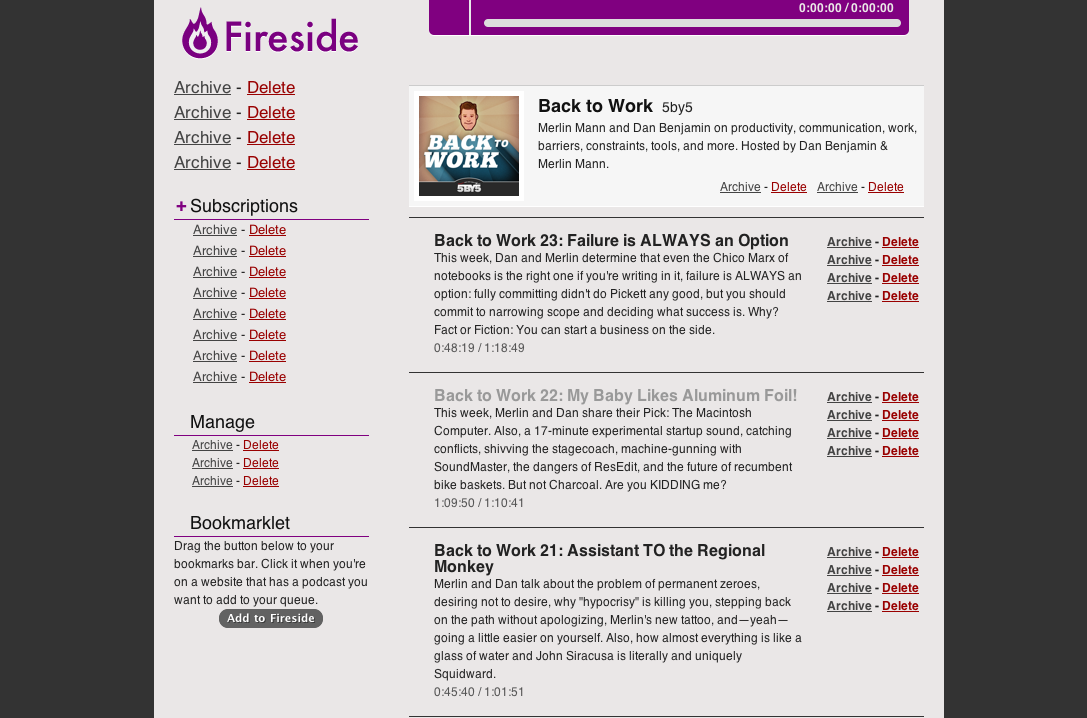

This solution makes us happy, because the e exponent portion approaches zero as t gets bigger, and the cosine portion just behaves in a cyclical manner. So over time, this will cyclically approach zero, which is perfect. We can graph it and see that it behaves the way we want it to.

Creating a KeyframeAnimation

To set up the CAKeyframeAnimation, we create a Keyframe Animation using a key path, which just tells the animation what properties to animate. You can find a full list of animatable properties and their key paths here on Apple’s site.

CAKeyframeAnimation *animation = [CAKeyframeAnimation animationWithKeyPath:@"position.x"];

animation.timingFunction = [CAMediaTimingFunction functionWithName:kCAMediaTimingFunctionLinear];

animation.duration = 0.2;

Next, we create an array to store the values of our animation. iOS will interpolate for us, but we create enough points so that the interpolation can just be linear. We use our damped oscillation function, and fill an NSMutableArray with values describing the motion. The values I chose, -0.3 and 0.35, were found by just experimenting, and finding values that had the number of bounces and duration that I wanted. You can calculate precise values by looking at the previous post and selecting values for m, c, and k.

int steps = 100;

NSMutableArray *values = [NSMutableArray arrayWithCapacity:steps];

double value = 0;

float e = 2.71;

for (int t = 0; t value = 320 * pow(e, -0.055*t) * cos(0.08*t) + 160;

[values addObject:[NSNumber numberWithFloat:value]];

}

animation.values = values;

We calculate values for our animation for each step, and add these values to our values array. I’ve added a little math to make sure that the function provides the right value to change position.x (the position of a layer corresponds to the center of a view ). CAKeyframeAnimation also lets us set timing functions for each step and the specific times that each step should occur at, but they’re unnecessary for this.

[upperView.layer setValue:[NSNumber numberWithInt:160] forKeyPath:animation.keyPath];

[self.upperView.layer addAnimation:animation forKey:nil];

Finally, we set the keypath property for the layer to the final value. We attach it to the layer of the view we want to animate. If we don’t set the final value of the animation before attaching the animation, the layer will snap back to its original state after the animation is over, and it won’t work.

Implicit vs. explicit animations

iOS distinguishes between implicit and explicit animations. An implicit animation is the more common type, where we use the UIView class function +(void)animateWithDuration:. In this case, we’re using a explicit animation, where we create a CAAnimation object and attach it to the layer that we want to animate. This gives us much finer-grained control, but requires us to tell the layer what the final value for the keypath is.

Patents

When working with physics simulation in touch devices, you need to be wary of the patents that Apple and other companies have on this technology. Apple’s patents, as far as I know, only protect algorithms that use track touches to determine the user’s finger’s speed. Since that’s not involved here, we are safe to use it. If there is another patent that is related here that I haven’t mentioned, please send me a tweet or an email, and let me know.

SKBounceAnimation

If you’re just making a simple bounce animation, I highly recommend you use SKBounceAnimation. It makes it very easy to do all these things and takes the math out of it. All you do is set the number of bounces, and it takes care of the rest for you.

Warning: This is a pretty technical and intended to be background for the next post. Read on only if you want to learn about mechanics. It will help to have at least a high school education in physics.

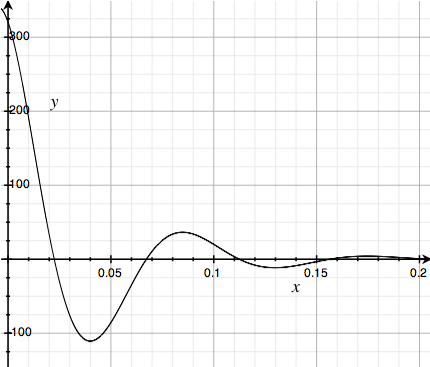

Since Apple’s introduction of momentum, friction, and bouncing in iOS, physical calculations have never been more relevant. In classical mechanics, a body that behaves this way is referred to mass-spring-damper system. If we want to create an element in our apps that animates and responds in a physical way, we have to understand the way these systems are modeled.

These motion of our system is dependent on three things:

The inertial effects are dependent on the acceleration and the mass (m) of the body,

The damping effect is based on the velocity of the body and some damping constant (c) (also referred to as _b _in some texts).

The bouncing effect of the spring is dependent on its displacement and the spring constant (k)

So, this is a fully second-order system, and requires hardcore differential equations to solve.

In a high school physics education, you might learn about inertial effects and forces from springs, but most likely not about dampers. A damper is, at its most high level, just a Newtonian fluid: it resists motion. The force that it imparts on the body is stronger when it is moving faster. It’s often modeled a dashpot, which you might be more familiar with as the rod that slows a screen door down. You can also imagine trying to move your hand in the pool: the faster your try to move your hand, the more strongly the water resists your motion, whereas moving slowly through the water is very easy.

The value of c can represent 4 states:

Over-damped: In this case, the damping effect is so strong that it doesn’t allow any oscillation (bouncing), before returning to its original position.

Critically damped: This is the lowest value of c that has no oscillation.

Underdamped: The damping is not strong enough, and the system overshoots and bounces while it returns to its original state. This is what we’re after.

No damping: The system doesn’t slow down at all and bounces forever.

Whether c represents an over-, under-, or critically damped system depends also on m and k.

A full derivation of our differential equation is unfortunately beyond the scope of this post. Rest assured that it’s really great and fun and you’re totally missing out. Once we solve the system given some initial displacement, we get this equation

where

and X represents our initial displacement, and t, the time after releasing our system from its displacement. To assure that the system is underdamped, we want ς to be less than 1 but greater than 0.

The next step is to use this equation to define the motion of our animated object using a CAKeyframeAnimation, which you can read more about in the next blog post.

I used images and equations from Wikipedia. Thanks to the folks there for creating them.